Mycotoxins are a costly, complicated problem for livestock and poultry producers. Not only are there hundreds of different mycotoxins, all produced by different fungi and environmental factors, but each category of toxins and each toxin within those categories can impact animals and birds differently. For producers, that means becoming aware of the major toxins and knowing the signs and symptoms of toxin exposure are critical to reduce the risk of mycotoxins eroding animal health and performance.

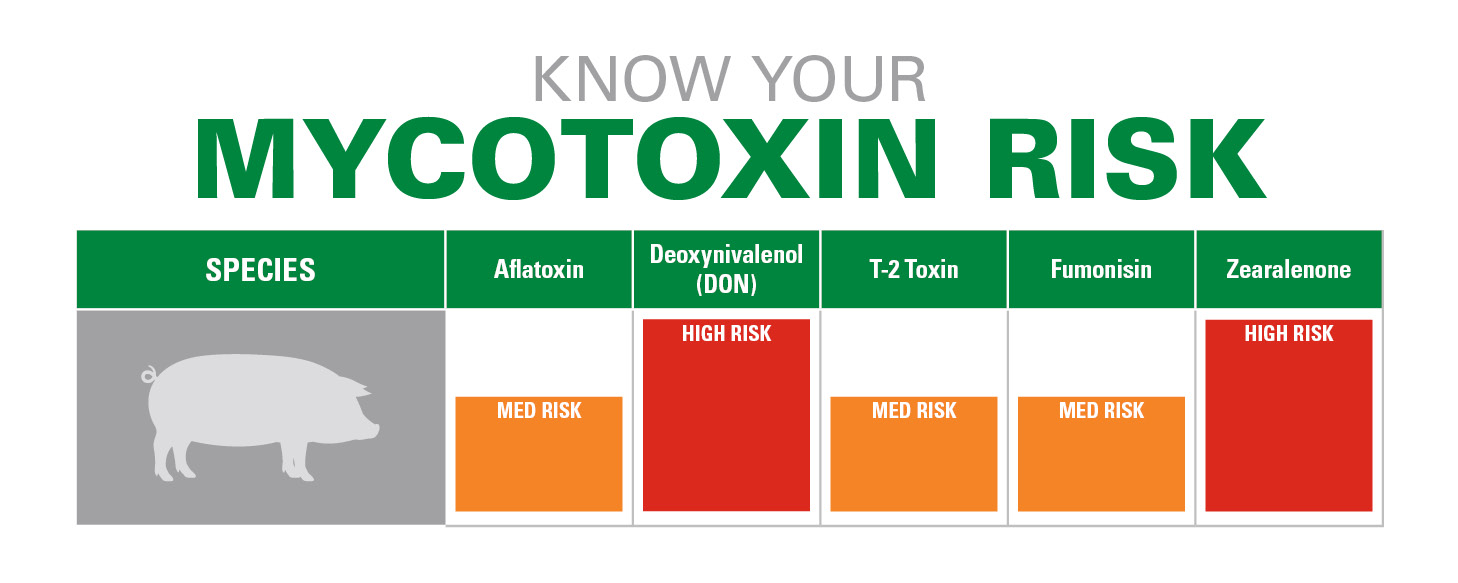

Of the hundreds of known mycotoxins, the five main profit-robbing mycotoxins of concern to livestock and poultry producers are: aflatoxin, deoxynivalenol, T-2 Toxin, zearalenone and fumonisin. Produced by Aspergillus species, aflatoxins are a group of chemicals considered carcinogenic (cancer-causing) to animals and humans.1 Trichothecenes, like deoxynivalenol (DON) and T-2 Toxin, are produced on many different grains like wheat, oats or corn by various Fusarium species. These toxins are frequently found together and can cause feed refusal and poor weight gain. Fumonisin can inhibit lipid metabolism, leading to immune suppression and nervous system damage. In swine, grain contaminated with fumonisin can also cause pulmonary edema. Zearalenone acts as an estrogenic molecule which can adversely impact reproduction. Fumonisin and zearalenone are also produced by Fusarium molds.