Many suppliers provide certificates of analysis for a fat source. They may include attributes like free fatty acid percentage, moisture, insolubles, unsaponifiables and other characteristics that relate to fat quality and digestibility. Unfortunately, these variables have little to do with oxidation potential. While peroxide values are often reported, peroxides alone are insufficient to know where a fat or oil is in the oxidative process. An increased understanding of fat quality, specifically the process of oxidation and oxidation markers, can help a producer determine their need for a supplemental antioxidant.

“Oxidation is a process, so customers need to know whether it’s just beginning or is already in advanced stages. When thinking about oxidation risks, we always urge our customers to ask the question: is the quality of the fat coming out of the storage tank equal to the quality when it went in?,” Tonda said. “Adding high-quality fats or oils to a storage tank containing residual lower-quality fat can dramatically reduce lipid quality and metabolizable energy within days. By looking at multiple measures for oxidation — peroxide levels, secondary oxidatives, like aldehydes and ketones, that form after peroxides — we can determine what phase it’s in i.e., to what extent oxidation has already happened and also get a feel for future oxidation potential."

Historical perspective on antioxidants

“Antioxidants have been in the livestock marketplace for decades, but with the increased knowledge about oxidative stress and its impact on animal health, the last 10 years have seen a rise in attention to antioxidants among nutritionists and producers,” Lamptey said. “Research in that time has shown more about the impact of fat quality on animal productivity, but liquid antioxidant products haven’t historically been an easy sell to producers who cycle through fat supplies frequently.”

“Some customers will say, ‘I get a load of fat every day. It doesn’t have time to get rancid,’” Lamptey said. “You can talk about the dangers in adding good fat on top of bad fat from now to next week, but without the right intervention, oxidation is going to happen. Even if the customer is going through one load of fat every day, the time spent transporting fat to the feed mill and the time it takes for feed manufactured using that fat to be consumed by the animal needs to be considered. Increasingly, antioxidants are becoming viewed as an inexpensive way to address quality control and risk management.”

Tactical antioxidant considerations for today’s producers

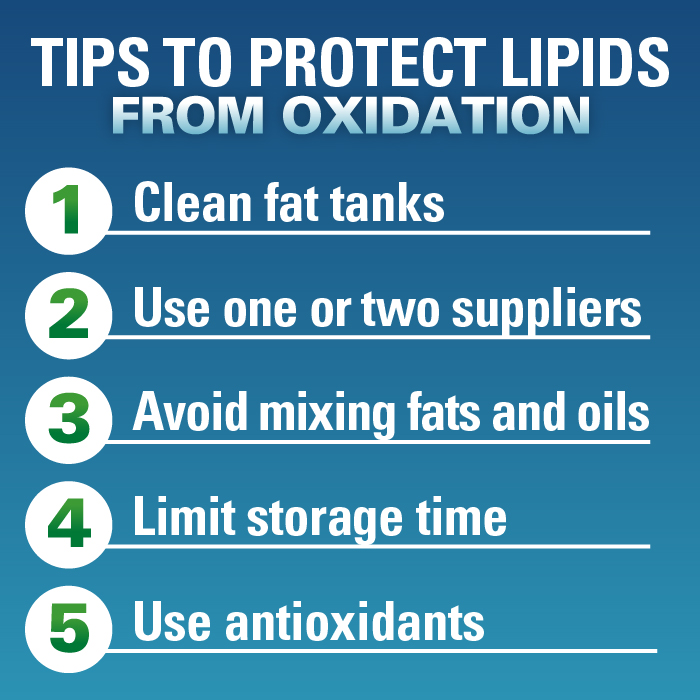

A critical first step in managing oxidation is cleaning fat tanks to ensure they’re free of residual fats that could cause oxidation in any future deliveries. Starting with a clean slate, a producer or nutritionist can add a high-quality fat source and an antioxidant to prevent oxidation and limit the harmful effects it can cause. While adding an antioxidant is a key part of that equation, it’s just as important to ensure you use an antioxidant that matches the lipid source being used. Antioxidants can vary widely in cost as well as efficacy. Synthetic antioxidants like ethoxyquin (EQ), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) or tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) are frequently used in traditional livestock and poultry diets; whereas, natural antioxidants are more commonly used in organic systems.

“Within our RENDOX® liquid synthetic antioxidant portfolio, we offer antioxidant formulations that are designed specifically for different fat types. For the best efficacy, matching the antioxidant molecule to the fatty acid profile of the lipid you’re using is key. For example, animal fats contain more saturated fatty acids, so an antioxidant, like BHA, BHT or EQ, will best protect those fatty acids. In contrast, vegetable oils like corn, soybean and canola have more polyunsaturated fatty acids, so an antioxidant like TBHQ is going to be more effective,” Tonda said. “While synthetic and natural antioxidants are both efficacious options for oxidation control, the biggest differences between them tend to be price – natural are more expensive – and dosage. Synthetic antioxidants tend to be more effective at lower inclusion rates than natural antioxidants.”

For most fat sources, inclusion of only one to two pounds of synthetic antioxidant per ton of fat is typically sufficient to provide the necessary antioxidant quantity needed to limit oxidation effects in stored lipids. However, the condition of the fat tank and quality of the incoming fat or oil can influence how quickly an antioxidant will be sacrificed.

Another aspect a producer should consider is the desired storage time of their finished feed. “Feed for production animals is typically consumed within days to a week or two of production, whereas a bag of retail feed might sit on a store shelf for six months before it’s purchased. The consumer expects good quality whether the feed has a shelf life of 1 month or 6 months,” said Lamptey. “This adds a challenge for producers making bagged feed. Whether or not you can achieve the desired shelf life is going to be the question for the consumer versus the feed mill operator or nutritionist for production animals.”

Irrespective of the source or type, all lipids go through oxidation because of their chemical nature. Producers have the ability to influence the rate at which oxidation happens by taking some preventive measures. Antioxidants offer one such inexpensive measure to support performance of healthy animals. If you’ve got oxidation concerns in your operation, start by discussing your lipid source with your feed supplier or nutritionist. Once you’ve confirmed your lipid source and identified the optimal product, learn more about RENDOX and the full line of Kemin antioxidant solutions.